I was twenty years old and enrolled in Baylor Law School. As a candidate for law review, I was expected to come up with two “publishable” law review articles. There was a list of suggested topics, and I chose the recent opinion in the case of Campbell v. Campbell, which dealt with the issue of whether Texas courts were entitled to divest title in separate property. I had no particular interest in domestic relations or marital property, but the Campbell case touched on an issue that was near and dear to my heart: the constitutional right of each person to retain his own property. While this right had only been implicit in the United States constitution, the Texas constitution made it explicit: the state may not take from one and grant to another.

I’m the sort of person who can’t write about something unless she actually cares. I can’t crank out articles for future gain alone. I didn’t really want to spend any of my spare time on a law review article. I had an unfinished novel that I was dying to work on that summer. But the topic of redistribution of wealth was important enough for me to take time out to write the required article.

So I researched, and I wrote, and I re-read and edited, until I thought I had a pretty good article. But when I submitted it, it was rejected.

Baylor Law School

- Baylor University | Texas Law School, Texas Law Schools, Texas Law School Admissions, Top Texas Law

Texas Law School Admissions. Baylor Law School is one of the finest law schools in Texas. - Baylor Law School – Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Baylor Law School is a small fully accredited institution where one can get some very good training in the practice of law. According to the Wikipedia article, “For students lucky enough to gain admission, Baylor’s unique, ultra intense, and ‘tough’ Practice Court Program is arguably the best training ground in the nation for practical lawyering…”

The problem for me is that I wasn’t all that interested in practical lawyering. I hadn’t a practical bone in my body. I was interested in theory, in right and wrong, in justice. Baylor just wasn’t a very good match for my strengths and weaknesses.

It’s not that I didn’t appreciate how lucky I was to have this opportunity at a legal education. There were many things that I liked about Baylor Law School. I loved the law library with its books from floor to ceiling. I savored my time in the student lounge with its real leather over-stuffed furniture where students actually hung around after classes were done. I appreciated the seriousness with which other students took their studies. Most of all, I loved the common law and the Socratic method.

What I didn’t like so much was the way cut-throat competition was fostered among the students by the faculty, the boot camp atmosphere that implied that stamina was more important than brains, and the way in which we were assigned so much material that it was impossible to read it all in a thoughtful frame of mind.

In short, I liked the academic standards, but disliked the professional training. I was interested in knowledge for its own sake, but Baylor Law School was a training ground for future trial lawyers. Many of my fellow students strove to excel because they hoped to get a good job once they graduated.

What did I want to do once I graduated? I had a list: 1) conquer the word 2) have my own law practice 3) write a novel 4) raise a child and a chimp together and teach them language.

Exactly how all these diverse activities were supposed to come together I did not know. For the time being, I went to law school full time and worked on my novel in spare moments.

Professor Simpkins

Loy M. Simpkins (Snake)

My favorite law professor was Loy M. Simpkins, nicknamed “Snake” by the students. He taught Marital Property and Trusts and Estates. These would not normally have been my favorite courses, as I was interested in contracts and constitutional law. As a libertarian, I believed in the sanctity of contracts, and I wanted to know all about any constitutional guarantees that might support individual rights. Marital Property was a highly suspect concept in my eyes, and I was not unaware of the subtle connection, both etymological and ideological, between community property and communism.

However, the professor who taught contracts stammered like porky pig, and the man who taught constitutional law believed that no right was absolute and that it was all negotiable and up to the politicians to decide. And then there was Snake! He kept our attention riveted throughout his lecture. He made Marital Property into a subject both deep and mysterious. “Section 3.63 of the Family Code,” he would intone, “says that the court may divide the estate of the parties in a manner that it deems just and right. But what exactly does that mean?” he would ask, twirling his mustache. And then, just when we thought it was merely a rhetorical question, he would turn to some hapless student and expect him to answer. Not just to answer, but to cite case law to support his position.

We talked amongst ourselves about how actually Snake knew exactly what section 3.63 of the Family Code meant, because he had been part of the team of experts who drafted the Family Code. He knew what section 3.63 meant, because he had written it himself! But he wasn’t telling. And so the courts would have to figure it out for themselves, since neither the legislative history nor the case law was clear on the topic.

Professor Simpkins loved to tell us hypotheticals in which the husband was labeled H and the wife was labeled W, and there was always some other woman also, originally named Tootsie, but who got renamed W2 after the divorce and second marriage. Sometimes in the middle of divorce proceedings, H would give Tootsie a gift “in fraud of the marriage”, and then the courts would have to decide whether the gift really belonged to the community estate and not to W2.

Snake was the editor/author of a tome entitled Speer’s Texas Family Law with Forms. Once, when I consulted this book, I noticed that under the dedication “To my wife” someone had penciled in “W2”.

Anyway, when I was told that as a candidate for law review, I had to choose a faculty member to sponsor and oversee my article, I chose Snake. I selected the Campbell decision because of its constitutional ramifications, but I chose Professor Simpkins because of his intimate knowledge of the Family Code. I didn’t think the constitutional law professor would be much use to me.

“Why, don’t you think he knows any constitutional law?” Snake asked, when I tried to explain why he was my first choice and not the “con law” professor.

I was embarrassed and did not meet his eyes. “No,” I said. “It’s just that I want to write something meaningful.”

Snake laughed. “I would think that for the chance at a $28,000.00 a year clerkship with a major law firm, you’d be willing to write anything that would get you on law review.”

All the way home I kept fuming to myself: “Does he think I would sell my soul for a mere $28,000 a year? I think my soul would be worth at least $50,000!”

But in retrospect, I don’t think that’s what Professor Simpkins meant at all. He just assumed all of us were in it for the money. And the reason I was so hurt by what he said was that it contained a grain of truth.

I did have a genuine interest in the law, but I had no wish to become a lawyer. My desire to write that particular law review article was sparked by an ardor for substantive due process and absolute property rights. But my interest in writing a law review article at all was due to the desire to succeed in the law school environment. Once arrived at law school, I found things that I liked and could genuinely care about. But the reason that I was in law school in the first place was not so pure. My parents had made it clear to me that I needed to make a living. They were affording me the opportunity to enter a profitable profession. In persuading me to go, they suggested that I might be able to do some good as a lawyer, as well as make a comfortable living. But it was the need to find a way to earn a living that had forced me down this particular path. I was hoping to finance all my other projects from what I made as a lawyer. In this way, if you examined what I was doing very closely, my actions were no more pure than those of anyone else.

I believed that it was all right to work for money. But it was not all right to do something for money that one would not wish to do otherwise. I would never write anything I did not believe in. Never!

And no, I didn’t want one of those $28,000 jobs. I would write the very best libertarian law review article on marital property that the world had ever seen! Snake was wrong about me.

When I finished the article and Professor Simpkins had read it, all he had to say was this: “Well, you certainly have given the matter a great deal of thought.” He made it sound as if this were a bad thing. But he approved my article, and I went ahead and submitted it to the Baylor Law Review.

When it was rejected, I asked for a meeting with Dean Dohoney to learn why. Dean Betty Dohoney was the assistant dean under Angus McSwain. She taught Civil Procedure, a subject I wasn’t much interested in, but that was of great practical importance. She was a straightforward, honest, direct sort of person, and her explanation made sense to me. “What you have written is more like a brief and less like a law review article,” she said. “In a brief, we advocate a position. In a law review article we don’t take sides. A law review article is just a survey of the law as it stands. It is meant to help practitioners who may be researching a case.”

Dean Dohoney told me that my article would count as one of the two publishable articles required in order to put “law review” on my resume. All I had to do was write another “publishable” article, and I’d have it made.

But I had an unfinished novel to work on waiting for me at home. If my law review articles were not going to be published, there didn’t seem to be much point in writing them. If in order to be published one had to refrain from saying anything important, then what was the point? If I was going to waste my limited free time working on something that would never see the light of day, it would be my novel. So I resigned from law review, and I finished my novel, and after it wasn’t published, I spent nine years as an independent attorney in my own law practice doing divorces. Luckily, my marital property professor had been an expert in the field! So my clients got a pretty good deal. And no, I never made anywhere near $28,000 a year — ever! But at least I was pure.

Years later, long after I had quit the law and gotten a Ph.D. in linguistics and was raising a little girl and a chimp all on my own, my grandmother died, and among her papers I found a yellowed manuscript held together with a rusty paperclip. It had been printed on a dot-matrix printer on thin cheap paper. Had I really given my grandmother a copy of my old law review article? I didn’t remember that! But anyway, just in case somebody else finds this of interest, here, nearly thirty years later, is the article I wrote….

Blindfolded Justice

Taking from One and Granting Another: Substantive Due Process in Marital Property

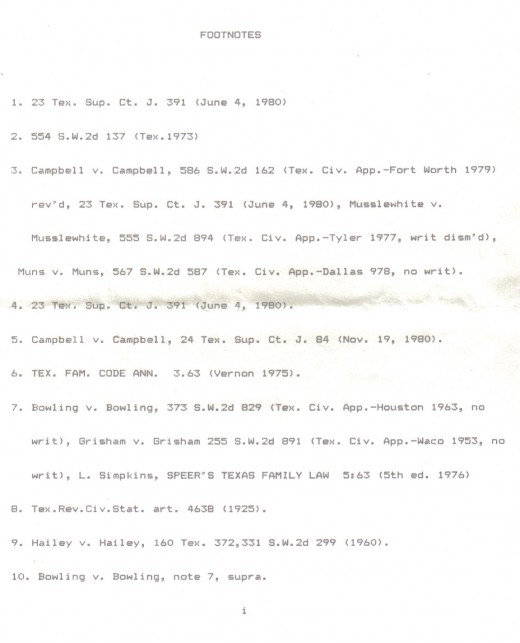

On June 4, 1980 in the case of Campbell v. Campbell1 (hereinafter Campbell) the Supreme Court of Texas held that section 3.63 of the Family Code does not sanction a divestiture of the fee in separate personalty. The trial court may not deprive one spouse of property acquired before marriage, or by gift, devise or descent, and give it to the other spouse.

The majority opinion in the Campbell case was brief. It stated in effect that the Eggemeyer v. Eggemeyer2 (hereinafter Eggemeyer) decision controlled. In Eggemeyer it was held that separate realty may not be taken from the one spouse and granted to the other. The Eggemeyer court gave several reasons for its holding, some statutory and some constitutional. It had not been totally clear whether all the arguments presented were necessary for the decision ultimately reached. Some courts chose to disregard the constitutional reasons given and followed the narrow holding of the case.3 In Campbell, the Supreme Court stated in effect: “Eggemeyer is stare decisis.”

After the Campbell decision had been handed down, the parties to the suit settled. The Supreme Court on motion for rehearing pronounced the case moot and withdrew its opinion on November 19, 1980. 5

What is the state of the law with regard to the divestiture of separate personalty? Of what precedential value is the Campbell decision? Is the Court likely to reverse itself?

Section 3.63 states: “In a decree of divorce or annulment the court shall order a division of the estate of the parties in a manner that the court deems just and right, having due regard for the rights of each party and any children of the marriage.”6

The statute is seemingly simple. Further inquiry into the history of division on divorce is required in order to arrive at the difficulty. It was for many years the law that a divorce court may divest a spouse of the fee to separate personalty, but not realty.7

The predecessor to section 3.63 was article 4638. Its language was nearly identical to that of section 3.63, but it further provided in its last sentence that the fee to realty should not be divested. For some time it was unclear whether the prohibition applied to community realty. In 1960 in Hailey v. Hailey9 the question was answered. The sentence forbidding divestiture of realty applied to separate realty only. All the while it was accepted law that on divorce the courts had wide discretion to dispossess a party of separate personalty.10

In 1970 section 3.63 was inserted in the Family Code.11 The legislative commentary stated: “This is a codification of present law.”12 Yet the last sentence containing the prohibition against divestiture of separate realty was omitted.13 The cause for such omission — whether by intention or inadvertence — would be of great interest to scholars of this area of Texas law. Whatever the reason for the change in wording from article 4638 to section 3.63, Texas courts were faced with interpretation of a seemingly new statute.

Some courts spoke of the great discretion vested in the trial court in division of the property of the spouses. In Baxla v. Baxla14the husband claimed that certain real estate was his separate property. The court answered his claim as follows: “While there is testimony which might contradict this position, we need not decide the issue. The court is given wide discretion in dividing separate property as well as community property…”15

In Wilkerson v. Wilkerson16 the wife claimed to own an undivided interest in certain land as her separate property. There the community was a tenant in common with the separate estate by virtue of separate contributions. It was held that the trial court is authorized to partition the land in kind or to divest the wife of her “equitable” title to property purchased partly with her separate funds. The court stated bluntly: “Had the legislature intended to limit the court’s authority only to a division of community property, it could have easily so provided.”17

But in Ramirez v. Ramirez18 the Corpus Christi Court of Appeals held that the trial court had erred in divesting the husband of title to his house and in granting it to the wife. It was held that section 3.63 does not empower a trial court to divest title to separate real estate. The court noted that had the legislature intended the courts to have such power, the word “estate” would have been in the plural.19

The Ramirez decision was eventually proved most correct.20 The argument with regard to “estate of the parties” was among the four espoused by the Supreme Court of Texas in the Eggemeyer decision.21 But the Eggemeyer opinion contained arguments of far greater reach.

In the Eggemeyer case the trial court had divested the husband of a one third interest in a farm as his separate property.22 The couple had four minor children, and the court imposed a lien on the property in the sum of $10,000.00 payable to the husband by the wife on the date when the youngest of the children attained to maturity.23

The Court of Appeals reversed the decision with regard to the separate property farm citing Ramirez v. Ramirez.24

Justice Pope delivered the opinion of the Supreme Court. He cited the case of Hedtke v. Hedtke as supportive of the proposition that upon divorce the income from a spouse’s separate property may be set aside for the support of minor children.25 It was noted that the trial court could have permitted the wife the use of the separate property for the benefit of the children during their minority.26 Such an act would have entailed no divestiture and would have been consistent with the requirement that a parent support his minor children.

The court referred to the legislative commentary that accompanied section 3.63 stating it was a codification of existing law.27 It was noted that there is nothing in the statute expressly authorizing divestiture of separate property.28 Section 14.05 of the Family Code which provides for putting aside of property of the parent for the support of a minor child was cited as further evidence that the legislature did not intend to alter the law with regard to the division of property on divorce.29 It had always been the law that a parent’s property could be set aside for the support of minor offspring. Divestiture of separate real estate had never been permitted. The court concluded that no change in the law had been intended and none effected.

Secondly, the statute speaks in terms of a division of the “estate of the parties.” The only estate in the singular is the community estate.30 The marital parties are cotenants in the the community estate. It is thus logically subject to division. Division in this usage is synonymous with partition — not divestiture.31

Chief Justice Andrew Jackson Pope

These were the statutory arguments in Eggemeyer. Had the court stopped here, perhaps the Campbell32case might have turned out differently. But the court continued.

Justice Pope cited Arnold v. Leonard33 as authority for the proposition that the constitutional definition of separate property is exclusive and may not be changed by the legislature. If section 3.63 were interpreted to allow the separate property of one spouse to be transformed into the separate property of another, the court would create a new type of separate property presently not in existence.34 This would be in violation of the definition of separate property in Article XVI, section 15 of the Texas Constitution.35

The last of the court’s constitutional arguments is the most important, for it has the potential to reach far beyond this area of marital property. Justice Pope referred to Article I, section 19 of the Texas Constitution36, providing that no citizen of the state shall be deprived of his property except by due course of law. This provision secures not only procedural, but substantive rights as well. In Marrs v. Railroad Commision37 the Texas Supreme Court relied on the statement by the United States Supreme Court to the effect that one person’s property may not be taken for the benefit of another private person without justifying public purpose.38 There was no benefit to the public from the taking of Mr. Eggemeyer’s property and its transfer to Mrs. Eggemeyer. Thus the taking was impermissible. The court wrote: “The taking from Homer would not have been a constitutional act even if the legislature had expressly authorized the divestiture of one person’s property and its vesting in another…” 39

This last was a great departure from accepted precedent. It may lead to a reexamination of the treatment of individual rights in the marital property field and elsewhere.

The Eggemeyer decision was followed by an incisive dissent by Justice Steakley, who addressed each of the majority arguments.40

Associate Justice Zollie Steakley

Justice Zollie Steakley

Justice Steakley stated that prior to the enactment of the Family Code a court was authorized to award all community property and all separate personalty to either spouse if it found such action to be “just and fair.”41 The fee in separate realty could not be divested, but only because the last sentence of article 4635 prohibited it.42 The dissent then cited precedent to the effect that when significant words are omitted from the reenactment of statute, there exists the presumption that the legislature “intended to exclude the object theretofore accomplished by the abandoned words.”43 Justice Steakley observed that the legislature had met in regular session four times since the effective date of section 3.63 and considered legislation to restore the prohibition.44 Yet it did not choose to do so.

While conceding the majority argument to be more grammatically sound, the dissent maintained that “estate of the parties” had long been established to mean “property” of the parties in this context.45

Justice Steakley asserted that transforming separate property of one spouse to that of another does not violate the constitutional definition. First, the property division under section 3.63 occurs after the dissolution of the marriage. The parties are no longer married. There can be no community property; all that is owned by each is owned separately.46 The dissent also noted that mutations of separate property and post marriage increases in value do not fit exactly into the Article XVI, section 15 definition.47 The Arnold v. Leonard implied exclusion is not uniformly applied. In Graham v. Franco48 the Supreme Court cited with approval the affirmative test of onerous effort.

The dissent indicated the majority to be mistaken in the belief that there was no justifying public purpose for the taking of separate property of one spouse and its transfer to another. The state has a pervasive interest in the marital relationship Justice Steakley asserted. Those who enter into matrimony knowingly subject themselves to present and future laws of the state governing the relationship.49

After Eggemeyer there was still much confusion with regard to divestiture of separate property. The first argument of the majority that section 3.63 was a mere reenactment of the previous law was misleading in view of the three remaining reasons. For if the law was now as it had been, while separate realty could not be divested personalty could.50 And yet if “estate of the parties” meant only the community estate separate personalty and realty alike were outside the scope of a “just and fair” division. Even more so if taking of separate realty during a divorce proceeding constitutes a taking against due course, there could be no different result in the taking of personalty. Numerous commentators speculated as to the real purport of the Eggemeyer decision.51

The question was resolved, at least in part, and for a brief space in time, by Campbell v. Campbell.52

In Campbell the trial court awarded the wife one half of the separate personal property of the husband — promissory notes in the face amount of approximately $11,200,000.53 The Court of Appeals upheld the trial court’s decision, reasoning that the holding in Eggemeyer is limited to separate real estate, the only type of property before the court in that decision.54 The Court of Appeals further stated: “We do not think it necessary or proper to give that decision a constitutional as opposed to a statutory foundation.”54

Curiously, the majority opinion in Campbell is penned by Justice Steakley, none other than the author of the striking dissent in Eggemeyer.55 The majority in Campbell concedes that there is some merit in the argument that the Eggemeyer decision deals with a different statutory problem from divestiture of personalty. Thus the first argument in Eggemeyer is not in conflict with the Court of Appeals’ decision in Campbell. “But this court went beyond the statutory problem in Eggmeyer and for the first time ruled upon constitutional grounds that title to the separate property of one spouse may not be divested and awarded to the other.”56 The majority thus concluded that with regard to the remaining three arguments the Eggemeyer decision is stare decisis and must be followed.57

Justice Joe R. Greenhill

The Campbell decision, like Eggemeyer, was followed by a much longer dissent. Justice Greenhill wrote the dissent, and his first observation was that the court will not pass upon a constitutional issue when the matter can be decided on a statutory basis.58 Thus, since Eggemeyer contained statutory grounds sufficient to uphold the ruling, the pronouncement on constitutional issues should not be used as precedent.

While quoting extensively from the Eggemeyer dissent, Justice Greenhill made two notable observations, The first of these is that the state does have an interest in the marital relationship.59 The second sheds a great deal of light on the history of section 3.63 and of Supreme Court decisions interpreting it.

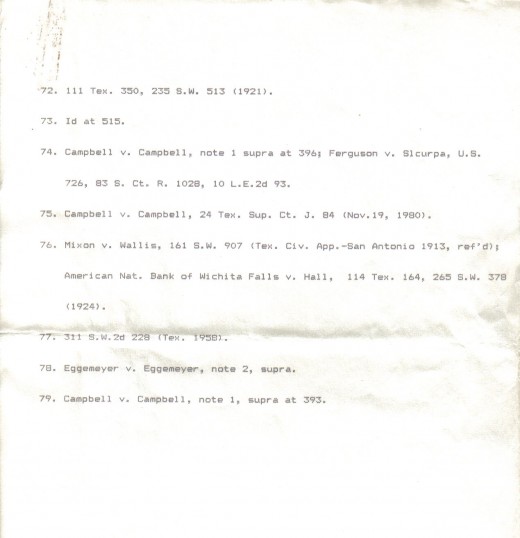

Justice Greenhill wrote: “The substantive due process of the court in Eggemeyer more nearly resembles that employed by the United States Supreme Court in the 1930’s to strike down laws it believed unreasonable, unwise or incompatible with some particular social or economic philosophy… Texas Courts could profit from the errors of the United States Supreme Court and refuse to engage in such ‘substantive due process’ which sets the court up as a super legislature.”60

Whether or not one subscribes to the dissent’s belief in its evils, substantive due process is undeniably at the heart of the Campbell and Eggemeyer decisions.

For many years it had been established precedent in Texas that separate personalty could be divested on divorce.61 The prohibition in article 463862 and its predecessors63 was itself proof by implication of the power of the legislature to provide for divestiture if it so chose.

It might be easily understood that the Supreme Court of Texas in Eggemeyer wished to correct a typographical error which had occurred during the passage of section 3.63. If separate realty had never been divested and the legislature no change in the law, the specific holding of the Supreme Court in Eggemeyer should not have been surprising.

Yet without the necessity of doing so, the court gave three other reasons for its decision — reasons that overruled established precedent a century old. The Campbell dissent noted that the Eggemeyer court did not need to make its constitutional holdings.64 one commentator observed that the court was informing the legislature that were it to change section 3.63 so as to specifically sanction divestiture, such provision would be struck down as unconstitutional.65 It may be further interjected that the due course argument was inserted in case of amendment of Article XVI, section 15.66 As a matter of fact, that provision of the Texas constitution has recently been amended.67 It now allows the parties by contract to alter the status of their property from community to separate.68 If the Eggemeyer decision had depended on that ground alone, it may be of little precedent today.

Justice Steakley in the Eggemeyer dissent asserted that the state interest in the marital relation justified a taking of the property of the one and its grant to the other spouse.70 The Campbell dissent made a similar statement.71 Such pronouncements evidence one of two distinct views of the governmental role in the marital relationship. The Eggemeyer and Campbell dissents imply that the marital relation helps in some way to preserve the state intact — that it serves the government. The state may thus regulate it to ensure that it functions in favor of governmental objectives.

The majority opinions in both Campbell and Eggemeyer did not address the issue. Yet it is possible to imply a reply from their silence. It may be that their view is that the state per se has no interest in marriage, but rather that the parties in the marriage have an interest in the state. In Spann v. City of Dallas72 the Supreme Court of Texas wrote: “The police power is subject to the limitations imposed by the Constitution upon every power of government; and it may not be suffered to invade or impair the fundamental liberties of the citizen, those natural rights which are the chief concern of the Constitution and for whose protection it was ordained by the people.”73 Justice Greenhill in his dissent stated that substantive due process has been in the past used “to strike down laws believed unreasonable, unwise or incompatible with some particular social or economic philosophy.”74

The philosophy in this case appears to be that of individual rights as opposed to governmental supervision.

On November 19, 1980 on motion for rehearing the Supreme Court withdrew its opinion in the Campbell case.75 The parties had settled[ the matter was therefore moot. The question remains: of what precedential value is Campbell?

There is some case law in Texas to the effect that when an appellate court withdraws an opinion, it should be treated as never rendered “in deference to the court’s wishes.”76 In Park v. Essa Texas Corporation77 a withdrawn opinion of the Supreme Court was held to be without force as precedent.78

If that be the case, one should proceed as though Campbell had never been passed upon, and the state of the law would return to its previous position under Eggemeyer. Yet the Campbell court indicated that Eggemeyer was stare decisis for the proposition that title to separate personalty may not be divested,79 and with all due deference to the Supreme Court’s wishes, the lower tribunals are not likely to ignore that pronouncement.

Copyright 1980, 2010 Aya Katz

Taking from one and granting another

Do you think the government should have to right to take property from one person and give it to another person, in any case other than for payment of a debt or in compensation for a tort?

- 17% Yes

- 83% No

12 people have voted in this poll.

In Case There’s a Fox

In Case There’s A Fox Buy NowO’Connor’s Texas Family Code Plus 2017-2018 Buy Now