When the government has done us wrong, any attempt to seek redress is fraught with difficulty. Ironically, people find it much easier to ask for a handout or a government job or a special favor than to ask for justice. The reason: before you can get justice, the party in the wrong has to admit to wrongdoing. Admission of misfeasance, even by a predecessor or an underling, is something that a government official is unlikely ever to do.

When the government has done us wrong, any attempt to seek redress is fraught with difficulty. Ironically, people find it much easier to ask for a handout or a government job or a special favor than to ask for justice. The reason: before you can get justice, the party in the wrong has to admit to wrongdoing. Admission of misfeasance, even by a predecessor or an underling, is something that a government official is unlikely ever to do.

Theodosia Burr Alston and Jean Laffite, each acting separately and under somewhat different circumstances, found themselves in the unenviable position of writing a letter requesting help from President James Madison in righting a wrong. The wrong, in each case, was not one committed directly by James Madison, but it was a wrong he had the power to redress and chose not to.

The mental gymnastics that petitioners must perform in order not to blame the person in power is of considerable interest. In this article I will compare the strategies employed by Theodosia Burr Alston in her letter to Dolley Madison of 1809 with those of Jean Laffite in his letter to James Madison of 1815.

Of the two, Theodosia Burr Alston was the better writer, which is not surprising considering her education and the fact that she was using her native language. But her ability

to conceal bitterness and deep seated anger toward those who mistreated her father is not equal to the task. In contrast, Jean Laffite manages to cast himself as a debonair benefactor who would never think of asking for anything but a return of his property, and at that he generously allows that he should be paid only so much as the United States Treasury can spare — implying that the country will remain forever in his debt.

The text of the letter to Dolley and the text of a similar letter Theodosia wrote to the Secretary of the Treasury, can be found here:

http://www.historiaobscura.com/theodosia-burr-alstons-letters-on-behalf-of-burr-in-exile/

Here I will quote relevant portions of the letter of June 24, 1809 from Theodosia Burr Alston to the first lady and will discuss their significance.

You may, perhaps, be surprised at receiving a letter from one with whom you have had so little intercourse for the last few years. But your surprise will cease when you recollect that my Father, once your Friend, is now in exile; and that the President only can restore him to me & to his country.

This is how the letter to the first lady starts, and while it may seem respectful and humble, the phrasing is already problematic. Theodosia is reminding Dolley of their long acquaintance at the same time as she admits there has not been much communication between them in the last few years. This lack of communication cannot have been because Theodosia wished it. In the last few years Aaron Burr dropped from the high office of Vice President to becoming a hunted fugitive. He was accused of treason by Thomas Jefferson himself. And when he was acquitted of the charge, despite Jefferson’s efforts to pressure the judge in the case, Burr was forced to flee the country. Not too long ago, Burr and James Madison had been close friends, Burr serving as a sort of wiser, more powerful mentor. Madison was also good friends with Jefferson. The alliance with Jefferson led to Madison’s being elected president. When forced to choose between his friendships with Jefferson and with Burr, Madison chose Jefferson. So it must be that James and Dolley, once regular dinner guests, dropped the Burrs as soon as they were in trouble.

What’s more, Theodosia reminds Dolley that Aaron Burr had once been her friend. Aaron Burr had helped bring the Madisons together. He had introduced Dolley to the future president. If not for him, Dolley would not now be Mrs. Madison.

All these things are true, but is it politic to bring them up in the opening paragraph of a letter in which you hope to get help from the president? Would it be better not to mention any of that? If Aaron Burr had been Dolley Madison’s friend, would she not remember it on her own? Isn’t an opening like that equivalent to saying: “You owe us”? And isn’t that what we must never say to anyone, leastwise someone in power?

Ever since the choice of the people was first declared in favor of Mr Madison; my heart, amid the universal joy, has beat with the hope that I too should have reason to rejoice. Convinced that Mr. Madison would neither feel nor judge from the feelings or judgment of others, I had no doubt of his hastening to relieve a man whose character he had been enabled to appreciate during a confidential intercourse of long continuance; and whom he must know incapable of the designs attributed to him. My anxiety on this subject has, however, become too painful to be alleviated by anticipations which no events have yet tended to justify; and in this state of intolerable suspense, I have determined to address myself to you, & request that you will, in my name, apply to the President for a removal of the prosecution now existing against Aaron Burr; I still expect it from him as a man of feeling and candour, as one acting for the world & posterity.

Among the universal joy that James Madison had been elected president, Theodosia added her own, based on the belief that this good friend of her father would now remove the “prosecution now existing against Aaron Burr”. She was sure that the moment James Madison came into office, her father’s troubles would be over, since they were good friends of long standing, and Madison knew that her father was not a traitor. And yet… Madison has been in office for a year now, and nothing has changed for Aaron Burr.

Again, there is no direct recrimination, but the context cries: “What kind of friend is James Madison? For that matter, what sort of President is he? He knows Aaron Burr is not guilty, knows that he was acting in the best interest of the country, and still he allows the prosecution to continue? To whom is he beholden for his office, that he cannot undo the harm that has been done?”

Statesmen, I am aware, deem it necessary that sentiments of liberality, and even justice, should yield to consideration of policy; but what policy can require the absence of my Father at present? Even had he contemplated the project for which he stands arraigned; evidently to pursue it any further would now be impossible. There is not left one pretext of alarm even to calumny; for, bereft of fortune, of popular favor, & almost of friends, what could he accomplish? And, whatever may be the apprehensions or the clamors of the ignorant & the interested, surely the timid illiberal system which would sacrifice a man to a remote & unreasonable possibility that he might infringe some law, founded on an unjust, unwarrantable suspicion that he would desire it, cannot be approved by Mr Madison, and must be unnecessary to a President so loved, so honoured. Why, then, is my Father banished from a country for which he has encountered wounds & dangers & fatigue for years?

Now, the recriminations are not implicit any longer. Every line screams: “This is so unfair!” And not far behind is the thought: “If Madison allows it, then Madison is unfair.”

And in case Dolley has forgotten, Theodosia recites the list of wrongs committed against her father and his current financial situation. She hints that he has no pension, like many other military heroes, and must start saving for his old age.

Why is he driven from his friends, from an only child, to pass an unlimited time in exile, and that too at an age when others are reaping the harvest of past toils, or ought at least to be providing seriously for the comfort of ensuing years? I do not seek to soften you by this recapitulation. I wish only to remind of all the injuries which are inflicted on one of the first characters the United States ever produced.

Theodosia is very proud. She hastens to assure Dolley that Burr will not steal into the country illegally when the country is still beholden to him for his services.

Perhaps it may be well to assure you there is no truth in a report, lately circulated, that my Father intends returning immediately. He never will return to conceal himself in a country on which he has conferred distinction.

Perhaps the most bizarre portion of the letter is this plea for secrecy. Theodosia is writing this letter behind her husband’s back, and she does not want him to find out about it. She implies that there is something almost improper in asking Dolley to speak to James Madison on Burr’s behalf. But already in so writing, she anticipates that her plea will be denied.

To whatever fate Mr Madison may doom this application, I trust it will be treated with delicacy; of this I am more desirous as Mr Alston is ignorant of the step I have taken in writing to you; which perhaps, nothing could excuse but the warmth of filial affection; if it be an error, attribute it to the indiscreet zeal of a daughter whose soul sinks at the gloomy prospect of a long and indefinite separation from a Father almost adored; and who can leave unattempted nothing which offers the slightest hope of procuring him redress. What indeed, would I not risk once more to see him, to hang upon him, to place my child on his knee, and again spend my days in the happy occupation of endeavoring to anticipate all his wishes? …

The tone of the letter turns desperate and melancholy and almost embarrassingly personal. That Theodosia’s love for her father knew no bounds is clear. But the phrase “What, indeed, would I not risk..” begs the question: what is she risking by writing this letter? Is writing to Dolley dangerous? How? Was Theodosia just being melodramatic or was more at stake than we know in keeping the correspondence with the first lady a secret?

Let me entreat, my dear Madam, that you will have the consideration and goodness to answer me as speedily as possible; my heart is sore with doubt and patient waiting for something definitive. No apologies are made for giving you this trouble, which I am sure you will not deem irksome to take for a daughter, an affectionate daughter, thus situated. Inclose your letter for me to A. J. Frederic Prevost, Esq., near New Rochelle, New York.

That every happiness may attend you, …

This letter, written from one woman to another, is at times angry, at times proud and at other times submissive and cloyingly sentimental. That Theodosia is desperate and would do anything to help her father is evident. But how effective is this letter in achieving her goals? Is her resentment toward the Madisons not just below the surface? Is it any wonder that Dolley turned her down, calling her a “precious friend” and otherwise complimenting Theodosia, but asserting that Mr. Madison could do nothing “to gratify” her wishes?

That was back in 1809. Theodosia was not asking for money or appointment to office or even a letter of marque. She was asking that her father be restored to his country, seemingly a very humble request. Why couldn’t it be granted? What forces outside President Madison’s control prevented it?

We turn now to Jean Laffite’s letter to James Madison written in December 27, 1815. Here the matter was simpler and more straightforward. Jean Laffite had informed the government of Louisiana and through them the United States Navy of the attempts of the British to recruit him to fight the Americans during the British attack on New Orleans. He offered to serve the Americans, and he gave proof of his loyalty by disclosing the whereabouts of the British fleet. Instead of accepting his overture, the American Navy and Revenue Service attacked the Laffite fleet in Barataria and confiscated his ships and the contents of his storehouse. Despite this, the Laffites remained loyal to the Americans and as soon as Edward Livingston had negotiated a deal for them with James Madison, going over the heads of the Governor and the Navy, the Laffites donated gunpowder and flint and served together with a company of their own trained artillerymen to turn the tide in the Battle of New Orleans. And yet after the war was over, the ships and goods that were confiscated from the Laffite brothers and their associates were sold at auction, never returned to their owners and no compensation was offered.

Here is the opening paragraph of Jean Laffite’s letter to James Madison, asking for restitution:

Encoraged by the benevolent dispositions of your Excellency, I beg to be permitted to State a few facts which are not generally Known in this part of the union, and in the mean time Sollicit the recommendation of your Excellency near the honnourable Secretary of the treasury of the U. S. whose decision could but be in my favour, if he only was well acquainted with my disinterested conduct during the last attempt of the Britanic fources on Louisiana. At the epoch that State was threatened of an invasion, I disregarded anny other consideration which did not tend to its Safety, and therefor retained my vessells at Barataria inspite of the representations of my officers who were for making Saile for Carthagena, as soon as they were informed that an expedition was preparing in New Orlean to Come agains us.

If  we disregard the spelling errors and the odd diction and style, we can see that Jean Laffite has placed himself in an advantageous position by failing to make any recriminations in the opening sentences.

we disregard the spelling errors and the odd diction and style, we can see that Jean Laffite has placed himself in an advantageous position by failing to make any recriminations in the opening sentences.

Unlike Theodosia Burr Alston in her letter to the first lady, who reminded Dolley of their relationship of long standing, Laffite, in his opening paragraph, casts James Madison as a fair, generous and disinterested party in this transaction who may not be fully acquainted with the facts of Laffite’s case. Also, in no way is Laffite soliciting funds from the President. It is the Secretary of the Treasury who needs persuading, and Laffite is hoping that James Madison will help win the Secretary over.

For my part I Conceived that nothing else but disconfidance in me Could induce the authorities of the State to proceed with So much Severity at a time that I had not only offered my Services, but likewise acquainting them with the projects of the ennemy and expecting instructions which were promised to me I permited my officers and Crews to secure what was their own, ashureing them that if my property Should be Ceized I had not the least happrehension of the equity of the U. S. once they would be Convinced of the Cinserity of my Conduct.

In other words, Laffite is so sure the United States government is fair and just, that he believes that only a misunderstanding of the facts of the case could have caused a delay in dealing fairly with him.

My view in preventing the departure of my vessells was in order to retain about four hunderd Skillful artillers in the Country, which Could but be of the utmost importance for its defence. When the aforesaid expedition arrived I abandoned all I pocessed in its power, and entered with all my Crews in the marshes, a few miles above New Orleans, and invited the inhabitants of City and its environs to meet at Mr. Labranches where I acquainted them with the nature of the danger which was not far of. (as may be seen by the anexed document which is atested by some of the moast notorious of the inhabitants which were present.) a few days after a proclamation of the Governor of the State permitted us to Joyne the army which was organising for the defence of the Country.

Laffite describes his behavior in putting the safety of the country first in very simple terms. He then goes on the explain that he wants no reward for defending the country, as anyone with patriotic feelings would do, but he wonders if he might have restitution for that portion of what the United States government took from him that would not deprive the United States Treasury of its own funds.

My Conduct Since that period is notorious The Country is Safe & I Claim no merit for having like all the inhabitants of the State, cooperated in its wellfair In this my Conduct has bin dictated by the impulce of my proper Centiments: But I Claim the equity of the Government of the U. S. upon which I always relied for the restitution of at least that portion of my property which will not deprive the treasury of the U. S. of anny of its own funs. For which benefit will lieve for ever grateful your Excellency’s very respectful and very humble & Obedeant Servant

Notice that in this way, Laffite puts himself not on the footing of one who seeks a favor, nor in the angry and bitter stance of one who has been robbed, but rather he paints himself as a benevolent and generous donor, who asks to have a little of what is his back, but not so much as to bankrupt the country or to put the Treasury out of business.

The problem, in Laffite’s case, was not with the content of the letter, but its execution. It was full of misspellings, awkward phrasing and malapropisms. As just one example, Laffite used the word “notorious” for its denotation, meaning “famous”, but not its negative connotation, “famous for being bad”. He is then seen as boasting about his ill fame, when he meant to say just the opposite.

Excuses could be made to the effect that Jean Laffite was not a native speaker of English, but that is not really the problem. James Madison was a gentleman, and he could read French, as very nearly all well educated men in those days could. In fact, the Madison archives contain letters addressed to the President in French requesting appointments and sponsorship. President Madison looked upon some of these requests with favor.

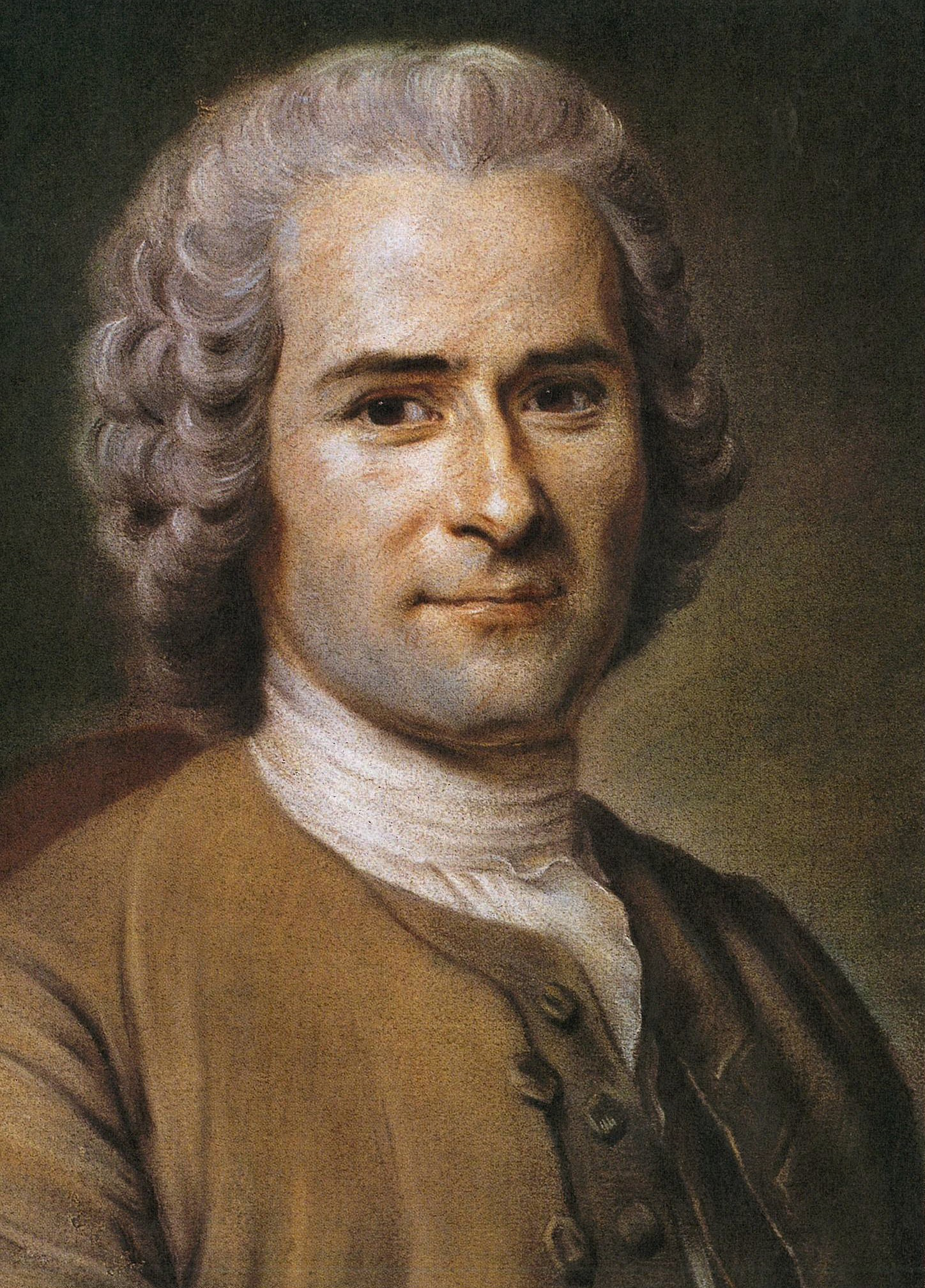

Letter from Dupont de Nemours to James Madison

As an example of just such a letter, consider the one dated December 28, 1815 from Dupont de Nemours to James Madison, which just happens to have been the next letter Madison received after the one he got from Jean Laffite. Dupont de Nemours writes: “Monsieur le President, J’ai a vous remercier avec la plus vive reconnaissance, a la bonte, pleine de graces, avec laquelle votre Excellence bien voulu admettre mon Petit-Fils dans le Corps de Midshipmen.” In English: “Mr. President, I have to thank you with the most vivid gratitude at the goodness with which Your Excellency has admitted my grandson into the Corps of Midshipmen.” In other words, for the grandson of Dupont de Nemours, an exiled French aristocrat, there is a place in the United States Navy. But for Jean Laffite, who saved the country from certain annihilation, there is nothing. Why?

The fact that Jean Laffite could not have written such a letter in French or English or any of the other languages he was fluent in is part of the story. Laffite was literate, in the sense that he could read and write. He was multilingual, in the sense that he spoke many languages fluently, among them Spanish, French and English. But he was no gentleman, in the sense that he did not have a university education or the equivalent of private schooling. No matter what language he wrote in, he was bound to make comical mistakes, such as spelling “sentiment” with a “c”. This word is spelled the same way in both French as in English, and it was not because Laffite was a Frenchman that he did not know how to spell it. It was because he belonged to the merchant class, and no matter how intelligent and brilliant and articulate he was, he could not compete with the likes of James Madison and Albert Gallatin and Dupont de Nemours.

Theodosia Burr Alston was a well educated woman who wrote brilliant, moving letters, but she could not move Dolley Madison, who was far less educated, especially when Theodosia reminded Dolley too often of the past in her letter. But Jean Laffite, despite his brilliant bargaining strategy was bound to fail like Theodosia in his plea to Madison, and his failure was for social reasons as well: Laffite’s way of expressing himself betrayed his class and confirmed in Madison’s mind that the man was nothing but “a pirate”.

REFERENCES

http://founders.archives.gov/?q=Theodosia%20Burr%20Alston&s=1511311111&r=5

Theodosia Burr Alston to Dolley Madison, 24 June 1809,” Founders Online, National Archives (http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Madison/03-01-02-0285, ver. 2013-06-26)

“To James Madison from Jean Laffite, 27 December 1815,” Founders Online, National Archives (http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Madison/99-01-02-4832, ver. 2013-06-26). Source: this is an Early Access document from The Papers of James Madison

http://memory.loc.gov/cgi-bin/ampage?collId=mjm&fileName=17/mjm17.db&recNum=871&itemLink=S?ammem/mjm:@field(TITLE+@od1(Jean+Laffite+to+James+Madison,+December+17,+1815+))

Suggested Reading

Buy it on Amazon!

we disregard the spelling errors and the odd diction and style, we can see that Jean Laffite has placed himself in an advantageous position by failing to make any recriminations in the opening sentences.

we disregard the spelling errors and the odd diction and style, we can see that Jean Laffite has placed himself in an advantageous position by failing to make any recriminations in the opening sentences.