A Christmas Carol Revisited: Analyzing George C. Scott’s Scrooge

[This article was originally published on Hubpages in 2010 and eventually de-indexed.]

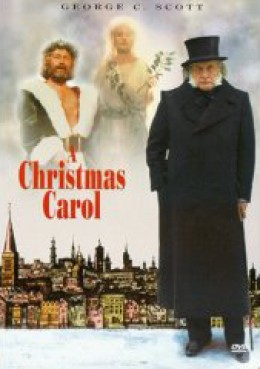

A poster of George C. Scott’s “A Christmas Carol” Source: Wikipedia

An Excerpt from A Christmas Carol

“At this festive season of the year, Mr. Scrooge,” said the gentleman, taking up a pen, “it is more than usually desirable that we should make some slight provision for the Poor and Destitute, who suffer greatly at the present time. Many thousands are in want of common necessaries; hundreds of thousands are in want of common comforts, sir.”

“Are there no prisons?” asked Scrooge.

“Plenty of prisons,” said the gentleman, laying down the pen again.

“And the Union workhouses?” demanded Scrooge. “Are they still in operation?”

“They are. Still,” returned the gentleman, “I wish I could say they were not.”

“The Treadmill and the Poor Law are in full vigour, then?” said Scrooge.

“Both very busy, sir.”

“Oh! I was afraid, from what you said at first, that something had occurred to stop them in their useful course,” said Scrooge. “I’m very glad to hear it.”

“Under the impression that they scarcely furnish Christian cheer of mind or body to the multitude,” returned the gentleman, “a few of us are endeavouring to raise a fund to buy the Poor some meat and drink and means of warmth. We choose this time, because it is a time, of all others, when Want is keenly felt, and Abundance rejoices. What shall I put you down for?”

“Nothing!” Scrooge replied.

“You wish to be anonymous?”

“I wish to be left alone,” said Scrooge. “Since you ask me what I wish, gentlemen, that is my answer. I don’t make merry myself at Christmas and I can’t afford to make idle people merry. I help to support the establishments I have mentioned — they cost enough; and those who are badly off must go there.”

“Many can’t go there; and many would rather die.”

Introduction

I’ve never really liked A Christmas Carol. Every time I’ve tried to read it, or have seen it performed, I kind of felt as if it was intended to be a direct slap in the face to me and my parents, and the values they taught me. “Don’t leave the light on. Turn the thermostat down. Don’t waste money. Don’t have a baby unless you can support it.” Those are the things I heard all my life. Scrooge embodies all those values, and when they knock him, they’re knocking me.

However, last year, because I was hard at work on The Debt Collector, I wanted to watch a performance of A Christmas Carol in order to experience first hand the kind of mentality I was up against. I was going to take my daughter to see the latest version at the local movie theater, but we somehow missed that. Also, a theatrical version was supposed to showing in the area, but nothing came of that, either. Finally, as a last resort, I went to Wal*Mart and bought two videos for the price of one, a sort of package deal. For the adults, there was George C. Scott in the starring role. And for children, there was some cheap cartoon version.

I asked Sword which one she wanted to see first. “Let’s watch the grown up one first,” she said. She was trying to be nice about it, since she imagined she’d probably like the cartoon better.

Scrooge is a Model of Filial Piety

In A Christmas Carol, much is made of Scrooge’s miserable childhood. His mother died in childbirth, bringing Scrooge into the world. His father, who loved his mother more deeply than words can tell, was grief stricken and blamed the infant for the mother’s death. As a result, Scrooge knew neither the love of a mother nor the support of an affectionate father figure. The only person who showed him any kindness was his elder sister.

Now, in this day and age, most would roundly condemn the father’s cruelty. He would be blamed for every failure in Scrooge’s life. Scrooge would go into therapy and learn to speak knowingly of abuse and neglect, casting aspersions on his father’s good name, and dodging responsibility for his own actions. “I was abused,” he would be taught to say. “It’s all my father’s fault. I can’t help it.”

And yet when the Ghost of Christmas Past shows Scrooge his miserable childhood, and he is forced to relive all those painful moments, moments that are best forgotten, Scrooge never says one bad word against his father. “He was stern,” is the most he can manage.

This remarkable stoicism, this refusal to point the finger or shift blame, is something that immediately made Scrooge rise in my estimation.

No parent is perfect. Some are better than others, but everyone makes mistakes. To spend your life blaming everything on your parents, instead of taking responsibility for your own actions is counterproductive.

The virtue of filial piety and of tight lipped stoicism in the face of soul crushing adversity is seldom praised. But we know it when we see it, and Scrooge has it in spades.

Scrooge is a True Gentleman in his Dealings with Women

Here is the short version of Scrooge’s love life: he hasn’t got any. The slightly longer version is this: he fell in love with Belle Fezziwig, and they became engaged. For years, he was satisfied with the engagement, but did not actually wish to marry. She, on the other hand, tired of waiting, called the whole thing off, and married somebody else. Scrooge, heart-broken, never stopped loving her, and he never took up with any other woman.

The evil spirits of Christmas that plague Scrooge accuse him of selfishness and greed. But let’s examine the facts here and see who exactly it was who was guilty of greed. Was it the man who asked nothing for himself, who enjoyed Belle’s companionship, but did not force himself on her body and soul? Or was it the woman who, the moment it was clear that Scrooge would never marry her, immediately went and found somebody else who would? Did she love Scrooge for himself, or only for the things he could give her: social position, wealth, sex, children? How great was her love? What was she willing to sacrifice to it? How great was his? What degree of self-restraint must it have taken of him not to make demands on her virtue? Don’t you think he wanted to sleep with her?

Keep in mind the back story. This was a man who was denied the love of a father, because his mother had died giving birth to him. His sister, also, died young, leaving a motherless boy. In those days, contraception was in its infancy, and a pregnancy often followed immediately after marriage. For all women, childbirth was painful and gruesome, and they often emerged scarred. Death in childbirth was not at all uncommon.

Did Scrooge refrain from marrying Belle because he did not love her enough, or because he loved her too much to risk killing her? At a time when sex, childbirth and death were so intimately intertwined, was it not the better man who preferred a platonic relationship over one that might very well destroy the object of his passion?

Scrooge, Charity and Government Welfare

Scrooge is needled for his stinginess, his miserly behavior and his risk aversion in general. He’s a party pooper and a loner and he doesn’t like Christmas. Who doesn’t like Christmas? His failure to support consumerism is a point of contention.

But the crux of the attack on Scrooge is his attitude toward the poor. When he is pestered by people soliciting for charity, he mentions that he already supports several public institutions whose purpose is to provide for the poor. Why should he contribute more, when these fine pillars of society already exist and are funded by his taxes?

The solicitors reply that many would rather die than go there.

So far, so good. Admittedly, Debtor’s Prison, the Poorhouse, and the Treadmill (whatever that is!) don’t sound very inviting. You might think that it’s because people in the nineteenth century were particularly cruel to others in unfortunate circumstances. But in fact, public institutions set up to “help the poor” are no kinder today. Social workers bully the people they are supposed to serve. Families under their supervision are broken up and destroyed. I have had clients who would rather become prostitutes than go on welfare.

The conclusion that logically follows from these all too true facts about public aid to the poor from the Dickens classic is that there should be no such institutions. However, this is not the conclusion that most people draw.

Why?

Paying for Love

It all comes down to love. There’s nothing more important than that.

Children are love. They are the greatest treasure that anyone can possess. The poor are sometimes quite wealthy, if we know how to look the right way. They are blessed with many children, but the thing to remember is this: these are blessings that they have bestowed on themselves.

Everyone, rich and poor, has the right to have children. Nobody, rich or poor, has the right to do so at somebody else’s expense. Love is a wonderful thing, and it’s okay to grab it when the grabbing is good, but there’s a price. Who should pay that price?

Should it be the person, like Scrooge, who didn’t allow himself to take the risk? Should he pay for somebody else’s love-making? Or should we each finance our own happiness?

Am I Scrooge? Not really. I have two children, one who is biologically mine, and one who is adopted. When I sit it in the dark and keep the heating costs down, I have them to keep me company, and we snuggle together. But I don’t have ten children. And it’s not because I wouldn’t like to have ten. I can’t afford them. And the earth can’t afford them, either. So I stick to the two I have.

Do you want to help others? By all means, do so. But don’t try to make other people feel guilty if they want to spend their money on something else. And if they don’t want to spend their money at all, then thank them kindly for the huge favor they are doing you. By failing to spend, they are enabling you to buy your Christmas pudding at a reduced cost, because the person who sells the pudding will have to lower the price, for lack of buyers.

If the moral of A Christmas Carol is anything, it is to “gather your rosebuds while ye may.” In other words: do not be risk averse, because tomorrow may never come. “Eat, drink, and make merry. Tomorrow we die.” But the moral that Scrooge urges on us is equally valid: “Make merry if you will, but don’t expect someone else to pay for your merrymaking.”

The Dickens Bias

Every person has a bias. The Charles Dickens bias stems from his own experiences early in life and from his own choices later in life. Dickens came from a nice, loving family, but his father spent more than he earned, and consequently what should have been a happy, middle class childhood was cut short when the family was sent to debtor’s prison.

What may have made it worse is that Dickens himself was separated from the others and made to work in blacking factory, a lower class work place. And so it was that a pampered boy from the middle class got to see what life was like for those born under less fortunate circumstances. This experience was humiliating and very painful, and it was one of the formative events of Dickens’ life.

Scrooge is the Anti-Dickens!

Dickens had a warm generous nature and with it an insatiable appetite for life. Like his father, in his adult life he was a big spender, but unlike his father, he was able to make his income match his expenditures by writing long, voluminous works, for which he was paid by the word. Dickens was a hack, but a very good one.

Dickens hated the poorhouse, but he himself actually opened a home for unwed mothers, where he hoped to educate these young women to do what he considered “better”. For someone who hated institutions that looked down on people, it was odd that he would want to found a few of his own to do the same sort of thing. Why should an unwed mother be institutionalized at all?

Unlike Scrooge, Dickens had an eye for the ladies, and he didn’t keep himself from enjoying the pleasures of the flesh. When an early paramour spurned him, he did not pine away for her forever, but found a nice substitute to marry. His married life was stormy, and over time he lost interest in his wife, but not before she had borne him ten children! When tired, overweight, and too lethargic to match the vigorous Dickens’ energy level, the wife no longer suited, he replaced her with a young actress and went touring the countryside.

Dickens was a genuine family man who enjoyed children, but he left most of the details of his children’s upbringing to the many women who came to serve him: first his wife, and then her sister who came to live with them. He spent money on sumptuous feasts and cozy living arrangements, and then he tried to earn money to cover his expenditures. He was a hard worker, but he was not frugal.

I don’t mean to begrudge Dickens his pleasures, and when I write this, I don’t want to come off as a prude. Dickens was a man, like all others, and it was understandable that he had needs, which he sought to satisfy. If he had done all this in private and kept his own counsel concerning the behavior of others, then I would not even mention it. But a paragon of virtue, he was not.

The same extremism that characterizes Scrooge’s miserly behavior seems to be found in Dickens, only in the opposite direction. Where Scrooge was stingy, Dickens was generous, and not always with money he had ready at hand. Where Scrooge was chaste, Dickens was profligate. Where Scrooge kept a tight lip and did not speak ill of his father’s misdeeds, Dickens publicized his own father’s neglect of duty and insolvency. Where Scrooge strove to lead a life of quiet desperation, asking nothing of anyone, and taking only what was his, Dickens was loud and boisterous and constantly asking for sympathy and money and love. Scrooge is the anti-Dickens!

In A Christmas Carol, which is a piece of propaganda, if ever a literary work was, Dickens urges the public: don’t be like Scrooge, be like me, instead!

I think most of us would rather not be like either one of them. There is, after all, a middle ground.

George C. Scott as Scrooge

The genius of George C. Scott’s portrayal of Ebenezer Scrooge is that he plays him as nobly as it is possible to do, within a script that is remarkably close to the original. I have seen simpering Scrooges and cowardly Scrooges, but George C. Scott’s Scrooge is a strong, brave, virtuous man, beset by the ghosts that all of us must face sooner or later. Does he have secret sorrows? Sure. Does he have regrets? Of course. Now that he is no longer young, does he maybe fear the cold, yawning grave that will swallow us all? Definitely. But he’s not spineless, and he isn’t evil. If you’re going to watch some version of A Christmas Carol this holiday season, I strongly recommend this one.

The movie came out in 1984, and has been playing on television for ages. Up until recently, this 1984 film classic was not available for purchase on videocassette or DVD, because George C. Scott held the copyright in his iron fist, and Scrooge-like would not let it go. But he died in 1999, and now you can buy a copy at Wal*Mart or on Amazon.

Our Personal Appraisal

I didn’t expect to like the movie as much as I did, but George C. Scott made a truly attractive, heroic figure of a Scrooge. He seemed so nice, that I could almost imagine being friends with him, and sitting in his dimly lit, unheated, inhospitable house, sharing a bowl of gruel and discussing the welfare state.

My daughter appreciated the movie more than I thought she would. She kept jeering at the ghosts throughout the viewing, asking why they didn’t just come in through the front door, like decent people. She also remarked early on, during the “bah humbug” sequences: “He’s just like grandma. She doesn’t like Christmas, either.” (And this is high praise for my mother, not a put down, by the way.)

The George C. Scott Scrooge obviously had Sword’s sympathy. The next evening, we watched the cartoon version. In the cartoon, Scrooge was portrayed as a mean, openly malevolent person who foreclosed on mortgages just for the pleasure of putting people out on the street, went out of his way to send the poor to debtor’s prison, and who spitefully threw things at Tiny Tim to make him sick.

Sword exclaimed: “Scrooge would never do that!” She had decided that George C. Scott was the real Scrooge, and she wasn’t buying the cartoon version at all. “Let’s not watch this,” she said. And so we turned it off.

(c) 2010 Aya Katz